Interstitial Lung Disease: Understanding Progressive Scarring and Current Treatment Options

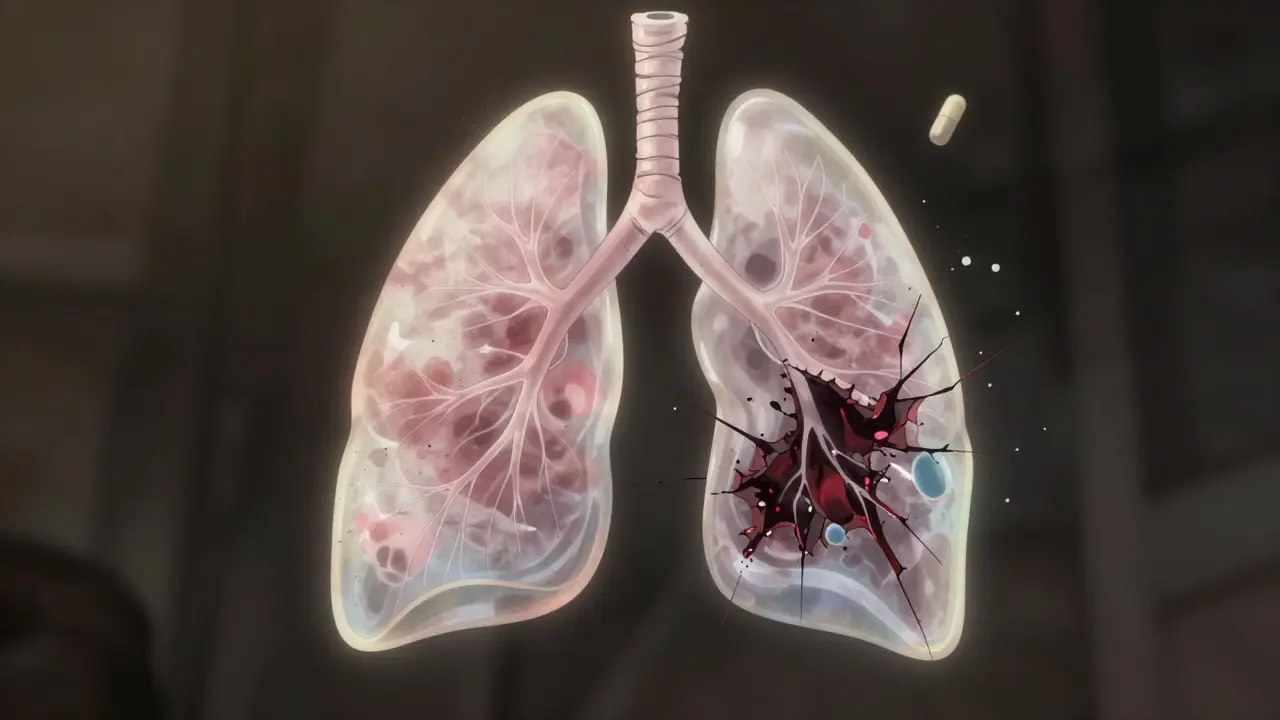

When your lungs start to stiffen and scar, breathing becomes harder-not just when you’re running or climbing stairs, but even sitting still. This isn’t just aging. It’s interstitial lung disease, a group of more than 200 conditions that slowly destroy the delicate tissue between your air sacs. Once this tissue turns to scar tissue, it doesn’t heal. The damage is permanent. But catching it early can change everything.

What Exactly Is Interstitial Lung Disease?

Think of your lungs like a sponge. The air sacs (alveoli) are the tiny holes, and the space around them-the interstitium-is the sponge material itself. In healthy lungs, this space is thinner than a sheet of paper. In interstitial lung disease (ILD), it thickens, hardens, and turns into scar tissue. That’s fibrosis. And that scar tissue doesn’t stretch. Your lungs can’t expand fully. Oxygen can’t move efficiently into your blood.

ILD isn’t one disease. It’s a category. Some forms are caused by known triggers-like asbestos, silica dust, or certain medications. Others, like idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), have no clear cause. IPF alone makes up 20-30% of all ILD cases. It’s the most common and aggressive type. Without treatment, the average survival is just 3 to 5 years after diagnosis.

The real danger? ILD sneaks up on you. Early symptoms are easy to ignore. You feel tired. You get winded faster. You think, "I’m just getting older." But by the time you’re struggling to breathe at rest, the scarring is already advanced. About 78% of patients report a dry cough. Nearly all have shortness of breath during activity. And by the time 35-50% develop clubbed fingers-those rounded, widened fingertips-the disease is well underway.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Most people go through a long, frustrating journey before getting the right diagnosis. On average, it takes 11.3 months from when symptoms start to when ILD is confirmed. Why? Because primary care doctors often mistake it for asthma, heart failure, or just aging.

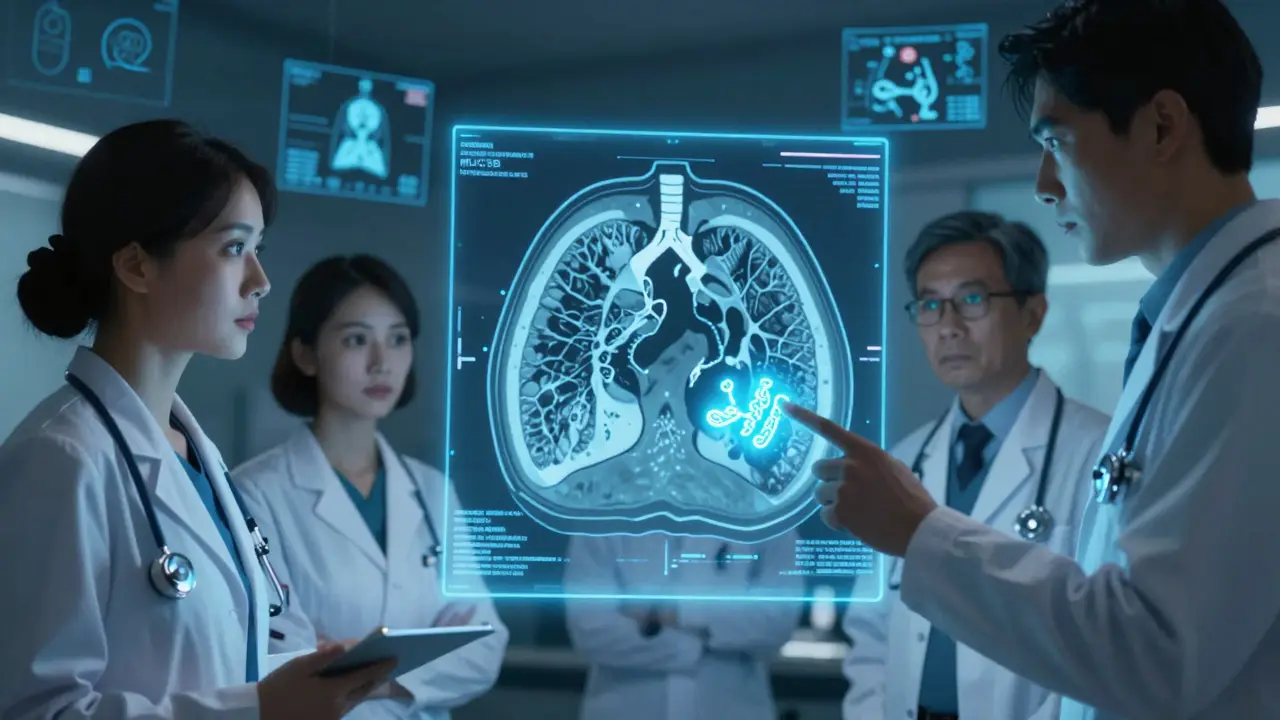

The gold standard is a high-resolution CT scan (HRCT). This isn’t your regular chest X-ray. HRCT takes 1mm slices of your lungs, showing the fine details of scarring. A radiologist looks for patterns: honeycombing, reticulation, traction bronchiectasis. These tell them what kind of ILD you have.

But scans alone aren’t enough. A multidisciplinary team-pulmonologist, radiologist, pathologist-must review everything together. In 85% of cases, this team approach changes the diagnosis. Without it, misdiagnosis happens in 25-30% of cases.

Doctors also use pulmonary function tests. If your forced vital capacity (FVC) drops by 20-50% and your DLCO (how well oxygen moves into your blood) falls by 30-60%, that’s a clear sign of ILD. The 6-minute walk test matters too. If you can’t walk 50 meters farther than you could a year ago, your risk of death triples.

What Causes the Scarring?

Not all ILD is the same. The cause changes how it behaves and how it’s treated.

- Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF): No known cause. Progresses steadily. FVC declines 200-300 mL per year. Median survival without treatment: 3-5 years.

- Connective Tissue Disease-Associated ILD: Linked to rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, lupus. Slower progression. 70-80% survive 5 years.

- Occupational ILD: Asbestosis, silicosis. Caused by long-term dust exposure. Progresses slower than IPF-about 100-150 mL FVC loss per year.

- Drug-Induced ILD: Caused by chemotherapy, heart meds, antibiotics. Often improves after stopping the drug.

- Radiation-Induced ILD: Happens 1-6 months after chest radiation. Permanent scarring in 30-50% of cases.

- Sarcoidosis: Inflammatory nodules, not always fibrosis. 60-70% resolve on their own within 2 years.

- Acute Interstitial Pneumonitis: Sudden, severe. 60-70% die within 3 months even with ICU care.

Some forms are treatable. Others are not. That’s why knowing the exact type matters more than anything.

Treatment Options: Slowing the Damage

There’s no cure. But there are ways to slow the scarring.

The two main drugs approved for IPF are nintedanib (Ofev®) and pirfenidone (Esbriet®). Both are antifibrotic-they don’t reverse scarring, but they cut the rate of lung function loss by about half over a year. Nintedanib costs about $9,450 a month. Pirfenidone runs closer to $11,700. Side effects are common: nausea, diarrhea, loss of appetite, and photosensitivity (pirfenidone makes your skin burn easily in sunlight).

For non-IPF ILD, these drugs often don’t work as well. That’s a major gap in care. A 2021 study in the New England Journal of Medicine pointed out that antifibrotics show little benefit for connective tissue disease or hypersensitivity ILD. That means treatment is still largely trial and error for many patients.

In September 2023, the FDA approved a new drug: zampilodib. It’s the first new antifibrotic in nearly a decade. In the ZENITH trial, it reduced FVC decline by 48% compared to placebo. It’s approved for progressive pulmonary fibrosis, not just IPF, which opens hope for more patients.

But drugs aren’t the whole story.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation: The Most Underused Tool

Most patients never hear about pulmonary rehab. But it’s one of the most effective interventions you can do.

A typical program lasts 8-12 weeks. You get 24-36 supervised sessions: breathing exercises, light strength training, education on energy conservation, and oxygen use. The results? Patients walk 45-60 meters farther in the 6-minute test. Their breathlessness improves. Their anxiety drops.

One study found that 72% of participants felt "moderate to significant" improvement. And it’s not just physical. People start leaving the house again. They stop canceling plans. They feel like themselves.

Yet only about 1 in 5 ILD patients are referred. Why? Many doctors don’t know how to order it. Insurance sometimes won’t cover it. But if you have ILD, this should be your first step-not your last.

Oxygen and Supportive Care

As ILD progresses, your blood oxygen drops. When resting SpO2 falls below 88%, you need supplemental oxygen. About 55% of IPF patients need it within two years.

Oxygen isn’t a cure. But it keeps you alive. It helps you sleep. It lets you walk farther without turning blue. Modern portable oxygen concentrators are lightweight and quiet. You can travel with them. You can sleep with them.

But managing oxygen brings its own challenges. Families spend 20+ hours a week helping with equipment. Filling tanks, cleaning tubing, troubleshooting alarms. Caregiver burnout is real.

Other supportive care includes:

- Flu and pneumonia vaccines (critical-lung infections kill ILD patients faster)

- Stopping smoking (if you still smoke)

- Managing acid reflux (it worsens scarring)

- Psychological support (anxiety and depression affect 68% of patients)

What’s on the Horizon?

The future of ILD is changing fast.

AI is now helping radiologists spot early scarring on CT scans. Mayo Clinic’s AI tool correctly identified ILD subtypes 92% of the time-better than human experts. That means earlier diagnosis.

Biomarker testing is another breakthrough. The MUC5B gene variant is now used to predict IPF progression. If you test positive, your risk of rapid decline is 85% higher. This lets doctors intervene sooner.

There are 26 active clinical trials for new ILD drugs. Some target inflammation. Others aim to reset scar tissue. Stem cell therapies are being tested. Combination treatments (two antifibrotics together) are in phase 3 trials.

And the big shift? Moving beyond just measuring lung function. Researchers now track how patients feel. Can they eat? Sleep? Walk to the mailbox? Patient-reported outcomes are becoming part of drug approval.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you or someone you love has unexplained shortness of breath, don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s aging.

- Ask for a high-resolution CT scan

- Request a multidisciplinary review

- Get tested for connective tissue diseases

- Ask about pulmonary rehab

- Find an ILD specialist-academic medical centers have dedicated clinics

- Join a support group. 78% of patients were misdiagnosed. You’re not alone.

ILD is not a death sentence. It’s a chronic condition-like diabetes or heart failure. With the right care, many people live years with good quality of life. The key is acting before the scars become too deep.

Can interstitial lung disease be cured?

No, ILD cannot be cured. The scar tissue in the lungs is permanent. But treatments like nintedanib, pirfenidone, and zampilodib can slow the progression of scarring. Pulmonary rehab, oxygen therapy, and lifestyle changes help manage symptoms and improve quality of life. Early diagnosis gives you the best chance to preserve lung function.

How fast does interstitial lung disease progress?

Progression varies widely. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) typically declines 200-300 mL in lung function (FVC) per year. Connective tissue-related ILD and occupational ILD often progress slower-100-150 mL per year. Some forms, like sarcoidosis, may improve on their own. Others, like acute interstitial pneumonitis, can be fatal within months. Regular monitoring with pulmonary function tests every 3-6 months helps track changes.

What are the side effects of antifibrotic drugs?

Pirfenidone commonly causes nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and photosensitivity-you burn easily in the sun. Nintedanib often leads to diarrhea, liver enzyme changes, and weight loss. About 65% of pirfenidone users report sun sensitivity, and 58% need dose adjustments due to stomach issues. These side effects are manageable with timing (taking pills with food), sun protection, and regular blood tests. Never stop the medication without talking to your doctor.

Is pulmonary rehabilitation worth it for ILD?

Yes, it’s one of the most effective treatments available. Studies show patients gain 45-60 meters in walking distance after a full program. Breathlessness improves, anxiety drops, and people return to daily activities. Yet fewer than 20% of ILD patients are referred. Insurance often covers it. Ask your pulmonologist for a referral. It’s not exercise-it’s education, breathing training, and energy-saving techniques tailored to your lungs.

Can I still travel with ILD and oxygen?

Yes, but you need to plan ahead. Portable oxygen concentrators are FAA-approved for air travel. Contact your airline at least 48 hours in advance to request oxygen services. Bring extra batteries-double what you think you’ll need. Always carry a copy of your prescription and a letter from your doctor. Many patients travel successfully with oxygen; it’s about preparation, not restriction.

How do I know if I have ILD or just asthma?

Asthma causes reversible airway narrowing-you wheeze, you use an inhaler, you feel better. ILD causes stiff, scarred lungs-you’re breathless even at rest, your cough is dry, and inhalers don’t help. Pulmonary function tests show different patterns: asthma shows obstruction; ILD shows restriction. A high-resolution CT scan is the only way to confirm ILD. If your symptoms don’t improve with asthma meds, ask for a CT scan and a specialist referral.

What’s the difference between IPF and other types of ILD?

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) has no known cause and progresses steadily, with a median survival of 3-5 years without treatment. Other ILD types have known triggers-like autoimmune disease, dust exposure, or drugs-and may respond differently. For example, sarcoidosis often improves on its own; drug-induced ILD can reverse after stopping the medication. IPF is the most aggressive and least responsive to immune therapies. Diagnosis depends on pattern recognition on CT scans and sometimes lung biopsy.

Are there any new drugs for ILD in 2025?

Yes. Zampilodib, approved by the FDA in September 2023, is the first new antifibrotic since 2014. It targets a different pathway than pirfenidone or nintedanib and is approved for progressive pulmonary fibrosis-not just IPF. Several other drugs are in late-stage trials, including combination therapies and agents that target inflammation or fibrosis at the cellular level. ClinicalTrials.gov lists over 20 active studies as of early 2025.

Comments

Joy Nickles

December 31, 2025 AT 07:25ok so i just got diagnosed with IPF last month and honestly i thought i was just getting old?? like i kept telling myself i’m out of shape but nooo it’s my lungs turning to cement?? this post literally made me cry and also google ‘pulmonary rehab near me’... thanks??

Emma Hooper

January 1, 2026 AT 18:56I’ve been in the ILD trenches for 4 years-pirfenidone turned my skin into a lobster and my stomach into a war zone, but I’m still here. And guess what? I took my grandkids to the zoo last weekend. With my oxygen tank. And I didn’t even care if people stared. You don’t have to be ‘normal’ to live well.

Marilyn Ferrera

January 3, 2026 AT 11:06The multidisciplinary team point is critical. I was misdiagnosed with asthma for 18 months. My pulmonologist finally insisted on an HRCT-and bingo. Honeycombing. Three weeks later, I was on nintedanib. Don’t let a generalist be your only doctor. Find an ILD center. Now.

Robb Rice

January 4, 2026 AT 23:55I appreciate the thorough breakdown of treatment options. However, I must note that while zampilodib shows promise, long-term safety data is still limited. As a caregiver to my mother with connective tissue ILD, I urge everyone to consult with a specialist before initiating any new therapy-especially off-label use.

Harriet Hollingsworth

January 5, 2026 AT 09:18People need to stop being lazy. If you’re breathing funny, go to the doctor. Not ‘maybe next week.’ Not ‘I’ll call my cousin who’s a nurse.’ Go. Now. And if your doctor says ‘it’s just aging’-find a new doctor. This isn’t a suggestion. It’s a survival tactic.

Deepika D

January 6, 2026 AT 22:15I’m from India and I’ve seen so many people ignore early symptoms because they think ‘breathing trouble’ means they’re just out of shape or stressed. But here’s the truth: in rural areas, no one gets HRCT scans. No one knows what IPF is. We need community health workers trained to spot dry cough + fatigue + clubbing. This isn’t just a medical issue-it’s a social justice issue. Let’s start local clinics with basic screening. I’ve volunteered to help train 50 community nurses next month. If you’re reading this and you’re in healthcare-join me. We can do this.

Darren Pearson

January 7, 2026 AT 11:32The notion that pulmonary rehabilitation is ‘underused’ is an understatement. It’s practically ignored by the medical establishment. A 2022 meta-analysis showed that rehab improves not only functional capacity but also reduces hospitalization rates by 41%. Yet, reimbursement policies remain archaic. This isn’t about patient compliance-it’s about systemic neglect.

Stewart Smith

January 9, 2026 AT 04:25So let me get this straight. We’ve got drugs that cost $11k/month, a new one that just came out, and the only thing that actually helps you feel human is… walking around a gym with a nurse telling you to breathe slow? And nobody’s talking about how ridiculous that is? I mean, I get it. But also… wow.

Sara Stinnett

January 11, 2026 AT 03:25Zampilodib? Really? Another overhyped pharma product disguised as hope. The ZENITH trial had a 7% dropout rate due to liver toxicity. And yet, the FDA approved it for ‘progressive pulmonary fibrosis’-a term so broad it could include someone who smoked a cigar in 1998. This isn’t progress. It’s profit.

linda permata sari

January 11, 2026 AT 12:10In my country, we say: ‘The wind doesn’t wait for the tired.’ My aunt had ILD. She didn’t have insurance. She didn’t have a specialist. She had us. We made her tea with ginger, sat with her when she couldn’t breathe, and held her hand when she cried. Medicine is important. But love? That’s the oxygen that keeps you alive when the machines fail.

Brandon Boyd

January 11, 2026 AT 19:51You’re not broken. You’re adapting. Every step you take with oxygen, every pill you swallow, every time you say ‘no’ to a party because you’re too tired-that’s not defeat. That’s strategy. You’re not giving up. You’re redefining what living looks like. And that’s brave as hell.

Branden Temew

January 13, 2026 AT 01:30So… we’re spending $10k/month on drugs that slow decline… but the real game-changer is breathing exercises and walking 6 minutes? And AI can spot scarring better than radiologists? Huh. So the future of medicine is… cheap, human, and quietly revolutionary? Who knew?