How Insurer-Pharmacy Negotiations Set Generic Drug Prices

Ever filled a prescription for a generic drug and been shocked by the price-even though you have insurance? You’re not alone. In 2024, 42% of insured adults in the U.S. paid more out-of-pocket for a generic medication than they would have if they’d paid cash at the pharmacy. That’s not a glitch. It’s how the system is designed.

Who’s really setting the price of your generic pills?

You might think your insurer or pharmacy sets the price of your generic medication. But the real power lies with Pharmacy Benefit Managers, or PBMs. These are the hidden middlemen between drug manufacturers, insurers, and pharmacies. Think of them as the negotiators behind the scenes. Three companies-OptumRx, CVS Caremark, and Express Scripts-control about 80% of the market. They decide which drugs are covered, how much pharmacies get paid, and what you pay at the counter.PBMs don’t just negotiate with drug makers. They also set reimbursement rates for pharmacies using formulas most people don’t understand. One common method is based on the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC), which tracks what pharmacies actually pay for drugs. But here’s the twist: PBMs often pay pharmacies less than that amount and charge insurers more. That gap? That’s called spread pricing. In 2024, PBMs made $15.2 billion from spread pricing alone-and most of it came from generic drugs.

How the pricing game works (and why it’s broken)

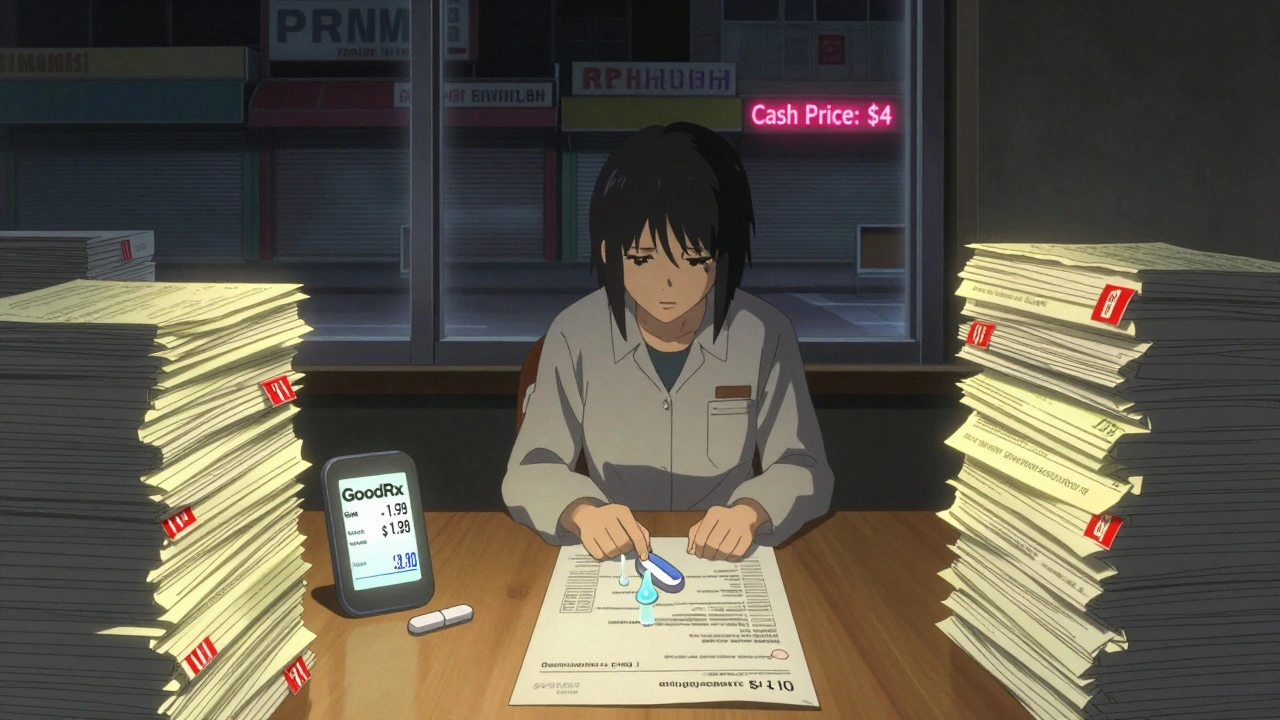

When you walk into a pharmacy with a prescription for a generic drug like metformin or lisinopril, the system kicks into motion. The pharmacy sends a claim to your PBM. The PBM checks its Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) list-a secret spreadsheet that says how much they’ll reimburse the pharmacy for that drug. That number is usually lower than what the pharmacy paid to buy it.Meanwhile, your insurer is charged a higher price-sometimes way higher. The difference? That’s the PBM’s profit. And because most plans don’t tell you what the real cost is, you end up paying a copay based on that inflated price. Even if the cash price at the pharmacy is $4, your insurance might make you pay $45 because the PBM’s system is rigged to make you think you’re getting a deal.

It gets worse. Many PBM contracts include gag clauses-legal restrictions that prevent pharmacists from telling you that paying cash would be cheaper. In 2024, 92% of PBM contracts had these clauses. That means your pharmacist can’t say: “Hey, this pill costs $7 if you don’t use insurance.”

Why your copay doesn’t reflect reality

Back in 1999, the average copay for a generic drug was around $5. Today? It’s still about $5.25. But inflation has risen over 60% since then. So why hasn’t your copay gone up? Because PBMs don’t want you to notice how much they’re charging your insurer. They keep copays low to make plans look affordable. Meanwhile, your insurer pays more behind the scenes-and you’re stuck with surprise bills.Some people think insurance always saves money. But for generics, that’s often not true. A 2023 Wall Street Journal investigation found patients paying for cancer and multiple sclerosis generics sometimes paid more with insurance than they would have paid cash. One Reddit user reported paying $45 for a generic blood pressure pill through insurance-while the same pill cost $4 cash. That’s not an outlier. It’s the norm.

The human cost of hidden pricing

This isn’t just about money. It’s about trust. Independent pharmacists are being squeezed. Between 2018 and 2023, 11,300 independent pharmacies closed because PBMs paid them so little they couldn’t cover costs. Many pharmacies now have to run two pricing systems: one for insurance, one for cash. That means more work, more software, more headaches.Pharmacists spend 200 to 300 hours a year just trying to decode PBM contracts. Some hire specialists for $100,000 a year just to understand how much they’ll get paid for a single prescription. And even then, PBMs can claw back money after the fact-taking back payments weeks after the prescription is filled. About 63% of independent pharmacies reported clawbacks in 2023.

Patients are confused. One survey found that 78% of complaints to the CMS Ombudsman Office in 2023 were about surprise bills-where the final price was 200% to 300% higher than expected. People aren’t just angry. They’re scared. Some skip doses. Others go without.

What’s changing-and what’s not

There’s pressure to fix this. In September 2024, the Biden administration ordered PBMs to stop spread pricing in federal programs like Medicare and Medicaid. That rule takes effect in January 2026. Fourty-two states are now passing laws requiring PBMs to disclose their pricing. The Pharmacy Benefit Manager Transparency Act of 2025 would force PBMs to pass all rebates straight to insurers.But here’s the catch: drug makers might just raise list prices to make up for lost rebates. And PBMs? They’ll find new ways to profit. The system is built on secrecy and complexity. Even if one loophole closes, another opens.

Meanwhile, programs like GoodRx and Cost Plus Pharmacy are giving people real alternatives. These services show you the true cash price-no insurance needed. In 2024, over 15 million Americans used them to pay less than $10 for common generics.

What you can do right now

You don’t have to wait for Congress to fix this. Here’s what works:- Always ask the pharmacist: “What’s the cash price?”

- Use apps like GoodRx, SingleCare, or RxSaver to compare prices across nearby pharmacies.

- If your copay is higher than the cash price, pay cash. Your insurance won’t know the difference.

- Call your insurer and ask: “Do you use spread pricing? Can you show me the actual reimbursement rate for my generic?”

- If you’re on Medicare, check if your drug is part of the new price negotiation program. Some drugs are now capped at $200 a year.

It’s not fair. It’s not transparent. But it’s not hopeless. The system is broken-but you have more power than you think.

Why is my generic drug more expensive with insurance than without?

Your insurance plan uses a Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) that charges your insurer more for the drug than it pays the pharmacy. The difference is called spread pricing, and it’s a hidden profit for the PBM. Your copay is based on that inflated price, not the actual cost. Often, paying cash directly at the pharmacy is cheaper.

What is a PBM and why does it matter?

A Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) is a middleman between drug makers, insurers, and pharmacies. They negotiate drug prices, create formularies, and set reimbursement rates. The top three PBMs control 80% of the market. They decide what you pay, what your pharmacy gets paid, and whether your pharmacist can tell you about cheaper cash prices.

Can my pharmacist tell me if cash is cheaper?

Legally, many can’t-because most PBM contracts include gag clauses that forbid pharmacists from disclosing cash prices. But since 2020, federal law has banned these clauses in Medicare and Medicaid. In 2024, 42 states passed laws requiring transparency. Still, enforcement is spotty. Always ask anyway.

Are generic drugs really cheaper than brand names?

Yes-on paper. Generics make up 90% of prescriptions but only 23% of total drug spending. But when PBMs manipulate pricing, the savings disappear. A generic drug might cost $4 cash but $45 with insurance. The problem isn’t the drug-it’s how the system charges for it.

What’s the difference between NADAC and AWP?

NADAC (National Average Drug Acquisition Cost) is the actual price pharmacies pay for drugs. AWP (Average Wholesale Price) is an outdated, inflated list price used by PBMs to set reimbursement rates. PBMs often use AWP minus a percentage, which creates artificial gaps between what they charge insurers and what they pay pharmacies.

Will the new Medicare drug negotiation laws help me?

Only if you’re on Medicare and your drug is one of the 20 selected for price negotiation. But the real impact will be indirect. As PBMs adjust to lower federal prices, they may lower rates for commercial plans too. Experts estimate the Inflation Reduction Act could save $200-250 billion over 10 years-if it spreads to private insurance.

What’s the best way to save on generics?

Use cash price apps like GoodRx or Cost Plus Pharmacy. Compare prices at different stores. Ask your pharmacist for the cash price before you pay. If it’s lower than your copay, pay cash. You’re not breaking any rules-you’re just using the system as it was meant to be used: to save money.

Comments

Larry Lieberman

December 9, 2025 AT 14:23This is wild. I paid $48 for my generic blood pressure med last month. Walked out and checked GoodRx-$5. I felt like I got scammed by my own insurance. 😱

Lisa Whitesel

December 9, 2025 AT 23:25People need to stop blaming insurers. PBMs are the real villains. No one talks about them because they’re invisible. Until we name the enemy, nothing changes.

Sabrina Thurn

December 10, 2025 AT 04:03The MAC lists and spread pricing are pure rent-seeking. PBMs aren't adding value-they're extracting it. The system is designed to obscure costs so patients never realize they're being gouged. It's economic predation disguised as healthcare.

Tejas Bubane

December 11, 2025 AT 02:24Another post about how broken the system is. Cool. But what’s your solution? More regulations? That’s just putting lipstick on a pig. PBMs will adapt. Always do. Stop crying and pay cash like the rest of us

Ajit Kumar Singh

December 12, 2025 AT 18:09I live in India we pay 50 rupees for metformin at local pharmacy no insurance no middleman no greed just medicine and people live longer here you think this is health care in USA its a financial engineering scam with pills

Andrea Beilstein

December 14, 2025 AT 05:34It’s not just about money. It’s about dignity. When your pharmacist can’t tell you the truth because of a contract you never signed, you lose trust in the whole system. That’s the real cost. And no spreadsheet can calculate that

Michael Robinson

December 15, 2025 AT 04:33They make you think insurance helps. But for generics? It’s like paying extra to get a discount. The math doesn’t work. You’re paying more to be part of the system. That’s not a deal. That’s a trap.

Courtney Black

December 15, 2025 AT 20:58I used to think PBMs were just middlemen. Turns out they’re the entire game. They control the rules, the scores, and the scoreboard. And we’re all just players who don’t even know we’re in a rigged casino. We think we’re playing poker. We’re actually playing Russian roulette with our prescriptions.

iswarya bala

December 17, 2025 AT 15:39omg i just checked my last script and it was $42 with ins but $6 cash i feel so dumb why didnt anyone tell me this sooner??

ian septian

December 18, 2025 AT 18:16Ask for cash price. Always. It takes 10 seconds. You’ll save hundreds a year. Do it.

Mona Schmidt

December 19, 2025 AT 12:01I’ve been a pharmacist for 17 years, and this is the most accurate summary I’ve ever read. We’re forced to run two pricing systems-one for insurance, one for cash. We get paid less than we pay for the drugs. We’re told not to tell patients the truth. We’ve watched 11,000 independent pharmacies close. And now we’re expected to be the face of a broken system while we’re the ones cleaning up the mess. The real tragedy isn’t the money-it’s the silence. We’re not allowed to speak up. But if you’re reading this, you’re not alone. And you’re not powerless. Ask for the cash price. It’s your right.

Sarah Gray

December 21, 2025 AT 00:40This is such a basic, elementary-level expose. Did you really need to write 2,000 words to state that PBMs are predatory? The fact that this is even a conversation is a testament to the collective intellectual laziness of the American public. I’m genuinely shocked anyone still believes insurance saves money on generics. It’s like believing your credit card gives you free money.

Angela R. Cartes

December 22, 2025 AT 23:18I just used GoodRx for my thyroid med. $3.50. My copay was $47. I’m done. 😤