Hatch-Waxman Act: How U.S. Law Made Generic Drugs Fast, Affordable, and Legal

The Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t just change how generic drugs get approved-it rewrote the rules of the entire U.S. pharmaceutical system. Before 1984, if you wanted to sell a copy of a brand-name drug, you had to start from scratch: run your own clinical trials, prove safety and effectiveness all over again, even though the original drug had already been approved by the FDA. That cost up to $2.6 million per drug in 1984 dollars-money most small companies didn’t have. The result? Few generics. High prices. Limited access.

What the Hatch-Waxman Act Actually Did

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, solved two problems at once. It protected innovators by giving them extra patent time to make up for delays caused by FDA reviews. And it gave generic manufacturers a shortcut-no more repeating clinical trials. Instead, they could prove their version was bioequivalent to the brand drug. That’s it.This shortcut came through the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). To file an ANDA, a generic company only needs to show:

- Their drug has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand drug (called the Reference Listed Drug, or RLD)

- It’s absorbed into the body at the same rate and to the same extent-bioequivalence

For bioequivalence, the FDA requires the generic’s blood concentration levels (Cmax and AUC) to fall within 80-125% of the brand drug’s. That’s not a guess-it’s a strict statistical standard backed by real pharmacokinetic data. If it passes, the FDA says: yes, this is interchangeable.

The Orange Book: The Secret Map to Generic Approval

The FDA doesn’t just approve drugs. It also keeps a public list called the Orange Book-officially titled Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations. Every brand-name drug listed here comes with a row of patents attached. These aren’t just any patents. They’re the ones that legally block generics from entering the market.Before a generic company can file an ANDA, they must check the Orange Book. Then, they pick one of four patent certifications:

- Paragraph I: No patents listed

- Paragraph II: Patents expired

- Paragraph III: We’ll wait until the patent expires

- Paragraph IV: This patent is invalid-or we won’t infringe it

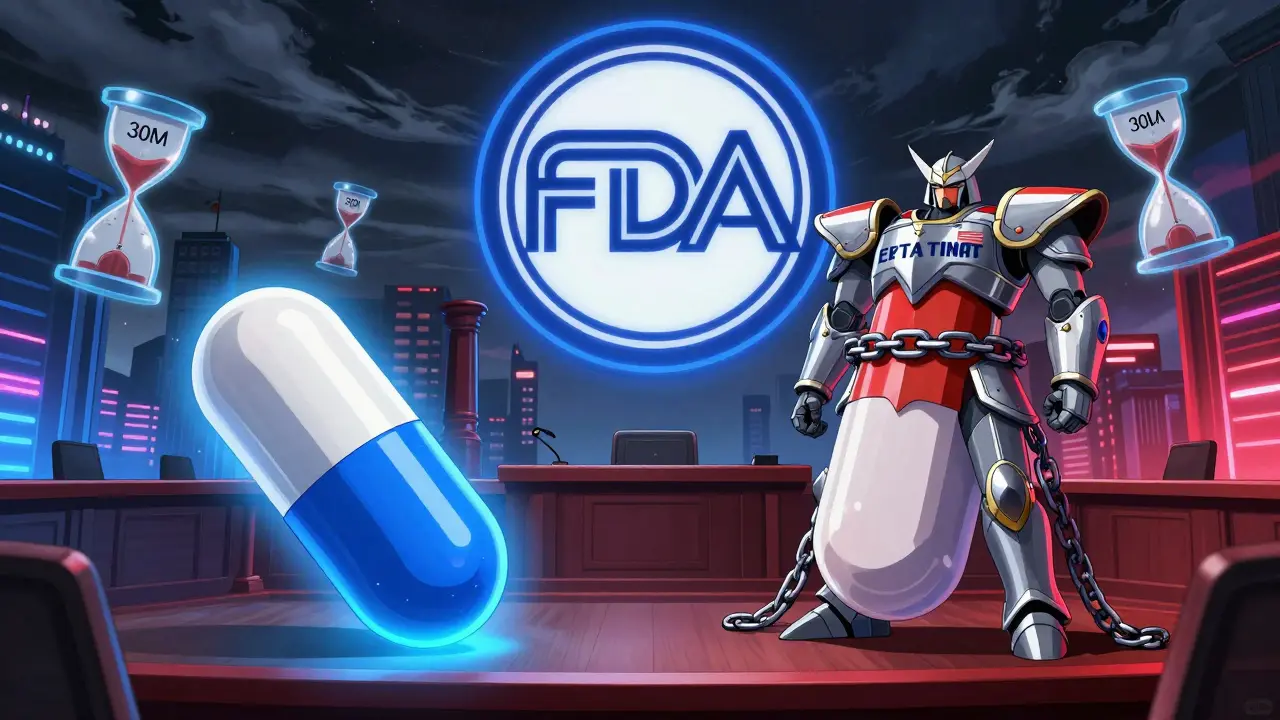

Paragraph IV is the big one. It’s the legal bullet that triggers a patent fight. The moment a generic company files a Paragraph IV certification, the brand-name company has 45 days to sue for infringement. If they do, the FDA is legally forced to delay approval for 30 months-or until the court rules, whichever comes first. That’s called the 30-month stay.

The 180-Day Prize: Why Everyone Races to File First

Here’s the kicker: the first generic company to file a successful Paragraph IV application gets 180 days of exclusive market rights. No other generic can enter during that time. That’s not a reward-it’s a financial jackpot.Why? Because during those 180 days, that single generic company can charge 80-90% less than the brand but still make huge profits. The brand drug might cost $500 a month. The generic might sell for $50. And with no competition, that first filer captures nearly the entire market. Companies have literally camped outside FDA offices to be the first to submit. In 2003, the FDA changed the rules so if two companies file on the same day, they share the exclusivity. But the race is still fierce.

And it works. According to the FDA, 90% of brand-name drugs face generic competition within one year of patent expiration. In 2023, the FDA approved 746 ANDAs-up from just a handful in the 1980s.

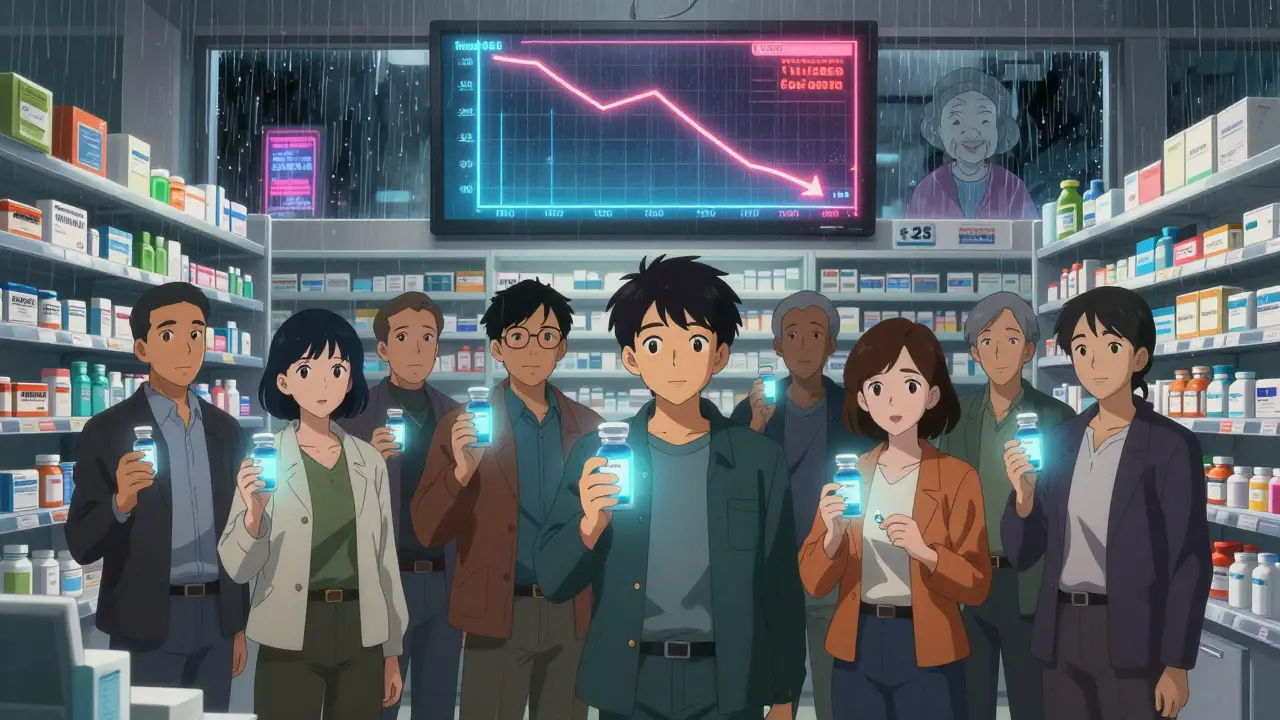

Who Wins? Who Loses? The Real Impact

The numbers speak for themselves. In 1984, generics made up 19% of prescriptions in the U.S. Today, they’re over 90%-by volume. But here’s the twist: they account for only 23% of total drug spending. That’s because they’re so much cheaper.The Congressional Budget Office estimates the Hatch-Waxman Act has saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.7 trillion over the past decade. Medicare Part D beneficiaries alone save an average of $3,200 per year thanks to generics. The generic drug market is now worth $70 billion annually in the U.S.

But it’s not perfect.

Brand-name companies have learned to game the system. They file dozens of secondary patents-on coating, packaging, dosing schedules-just to extend protection. This is called patent thickets or evergreening. The average drug has 1.5 patents listed when it launches. By the time generics enter, it’s often 3.5 or more.

Then there’s pay-for-delay. Sometimes, a brand company pays a generic manufacturer to delay their launch. The generic gets a cut of the brand’s profits. The brand avoids competition. The consumer pays more. The FTC has challenged dozens of these deals, but they still happen.

And not all drugs are easy to copy. Biologics-complex drugs made from living cells-can’t be replicated under Hatch-Waxman. That’s why Congress passed the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) in 2010. It created a separate pathway for biosimilars, but it’s slower and more expensive.

How Generic Companies Play the Game

Generic manufacturers like Teva, Mylan (now Viatris), and Sandoz have built entire departments just to navigate Hatch-Waxman. They hire patent lawyers, pharmacokinetic scientists, and regulatory specialists. It’s not cheap: the average ANDA now costs $5-10 million and takes 3-4 years to get approved.But the payoff is worth it. If you’re first to file a Paragraph IV and win, you can dominate the market for six months. After that, prices collapse. A drug that sold for $1,000 a month might drop to $10 within a year. That’s the power of competition.

What’s Changed Since 1984?

The FDA has kept up. The Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA) introduced in 2012 gave the agency more funding to hire reviewers. In 2012, the average ANDA review took 36 months. By 2023, it was down to 18 months. That’s huge.The CREATES Act of 2019 forced brand companies to provide generic makers with the drug samples they need to test bioequivalence. Before that, some brand companies refused to sell samples, effectively blocking generic entry. Now, if they don’t comply, they can be sued.

Still, challenges remain. In 2023, 283 generic drugs were in shortage. Many are old, low-margin drugs made by a handful of factories. Quality issues at foreign plants have also led to recalls. And as more complex drugs-like inhalers, injectables, and transdermal patches-come off patent, the FDA is struggling to keep pace.

Why This Matters to You

If you take a prescription drug, chances are it’s a generic. And if it is, you’re benefiting from the Hatch-Waxman Act. Without it, your insulin, your blood pressure pill, your antidepressant might still cost hundreds of dollars a month. Instead, you’re paying $10, $5, even $0 with insurance.This law didn’t just lower prices. It made healthcare more predictable. It gave doctors confidence that a generic is just as safe and effective. It gave patients access. And it forced innovation-not by stopping it, but by balancing it.

The Hatch-Waxman Act isn’t perfect. It’s messy, litigious, and sometimes manipulated. But for 40 years, it’s worked. And for the millions of Americans who rely on affordable meds, that’s what counts.

What is the ANDA pathway under the Hatch-Waxman Act?

The Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) is the streamlined approval process created by the Hatch-Waxman Act for generic drugs. Instead of running full clinical trials, generic manufacturers prove their product is bioequivalent to the brand-name drug by showing identical active ingredients, strength, dosage form, and absorption rate in the body. This cuts development costs and time dramatically.

What does Paragraph IV certification mean?

Paragraph IV certification is when a generic drug applicant claims that a patent listed for the brand drug is either invalid or won’t be infringed by their product. This triggers a legal challenge. The brand company has 45 days to sue for patent infringement, which then triggers a 30-month FDA approval delay. It’s the most aggressive-and potentially most profitable-strategy for generic companies.

Why does the first generic company get 180 days of exclusivity?

The 180-day exclusivity is an incentive to encourage generic companies to challenge weak or questionable patents. Since filing a Paragraph IV certification is risky and expensive, the law rewards the first filer with a temporary monopoly on the market. During those six months, they can capture most of the sales before other generics enter and prices drop.

Can all drugs be turned into generics under Hatch-Waxman?

No. Hatch-Waxman only applies to small-molecule drugs-traditional pills and injections made from chemical compounds. Complex biologics, like insulin or monoclonal antibodies, can’t be copied exactly. They require a separate pathway under the BPCIA of 2010, which creates biosimilars instead of generics. The process is longer, costlier, and less competitive.

How does the Orange Book help generic manufacturers?

The Orange Book lists every FDA-approved drug and the patents tied to it. Generic companies use it to identify which patents they need to challenge before launching. It’s the official map to the legal barriers. Without it, there would be no way to know which patents block entry-or when they expire.

Has the Hatch-Waxman Act been updated recently?

Yes. The most recent major updates include GDUFA (Generic Drug User Fee Amendments), which improved FDA review times, and the CREATES Act of 2019, which forced brand companies to provide samples for testing. Congress is still debating reforms to stop "pay-for-delay" deals and limit patent thickets, but no major changes have passed yet as of 2025.

Looking ahead, the FDA is working on new guidance for complex generics-like inhalers and long-acting injectables. As more of these drugs lose patent protection, the system will be tested. But for now, the Hatch-Waxman Act remains the backbone of affordable medicine in the U.S.

Comments

Natasha Sandra

December 26, 2025 AT 03:52This is literally why my insulin costs $10 instead of $500 😭 Thank you, Hatch-Waxman! 🙌 I don’t know how people survived before this law. 🤯

Rajni Jain

December 26, 2025 AT 22:56i read this and just cried a lil... my mom took generics for her bp pills for 15 yrs and never had a problem. so simple yet so powerful. 🙏

Fabio Raphael

December 27, 2025 AT 20:53I always wondered why generics are so cheap. The bioequivalence part is wild-80-125% range? That’s like saying your coffee can be 20% weaker or stronger and still be 'the same'. But I guess the data backs it up. Fascinating.

Amy Lesleighter (Wales)

December 29, 2025 AT 16:49people think generics are fake medicine but theyre not theyre the same stuff just cheaper. the system is broken but hatch-waxman fixed it enough to save millions

roger dalomba

December 30, 2025 AT 04:15Ah yes, the noble Hatch-Waxman. Where corporate lawyers outsmart regulators and generic companies gamble millions on patent bluffing. Truly, the American Dream™.

Nikki Brown

January 1, 2026 AT 02:45I can't believe people still don't understand that Paragraph IV is just legalized extortion. 🤦♀️ And don't even get me started on pay-for-delay. This isn't healthcare-it's Wall Street with a stethoscope.

Becky Baker

January 1, 2026 AT 04:40America built this system. No other country has this kind of innovation and balance. We lead the world in affordable meds. Don't let the haters ruin it.

Sumler Luu

January 3, 2026 AT 03:58I work in pharmacy and see this daily. The Orange Book is everything. Without it, we'd be flying blind. Still, the delays for complex generics? Brutal.

sakshi nagpal

January 4, 2026 AT 18:26It's interesting how such a technical law has such a profound human impact. In India, we don't have this structure, and generics are everywhere-but without the same regulatory rigor. There's a lesson here about balance.

Sandeep Jain

January 6, 2026 AT 04:50u know what sucks? when the only company that can make a drug is in china and then it gets recalled. hatch-waxman helps but supply chain is a mess

Brittany Fuhs

January 7, 2026 AT 19:18the fact that we need a 40 year old law to keep drug prices semi-reasonable says everything about how broken our system is. and now they wanna make biosimilars even harder? classic.