Idiopathic Orthostatic Hypotension & Anxiety: Understanding the Connection

IOH & Anxiety Symptom Checker

Answer the following questions about your symptoms to get insights into possible overlap between idiopathic orthostatic hypotension (IOH) and anxiety:

Ever felt light‑headed after standing up and then notice a racing mind that won’t settle? You might be juggling two hidden health issues that often feed each other: idiopathic orthostatic hypotension and anxiety. This article breaks down what each condition looks like, why they overlap, and what you can actually do to feel steadier-both in body and mind.

Key Takeaways

- Idiopathic orthostatic hypotension (IOH) is a sudden drop in blood pressure upon standing that isn’t explained by medication, dehydration, or another disease.

- Anxiety can trigger the same physiological stress responses that worsen IOH, creating a feedback loop.

- Common symptoms-dizziness, shakiness, heart palpitations-often blur the line between the two, making diagnosis tricky.

- Targeted lifestyle tweaks (hydration, salt, gradual position changes) and stress‑management techniques can break the cycle.

- Seek medical advice if symptoms persist, worsen, or cause falls, as early treatment reduces long‑term risk.

What Is Idiopathic Orthostatic Hypotension?

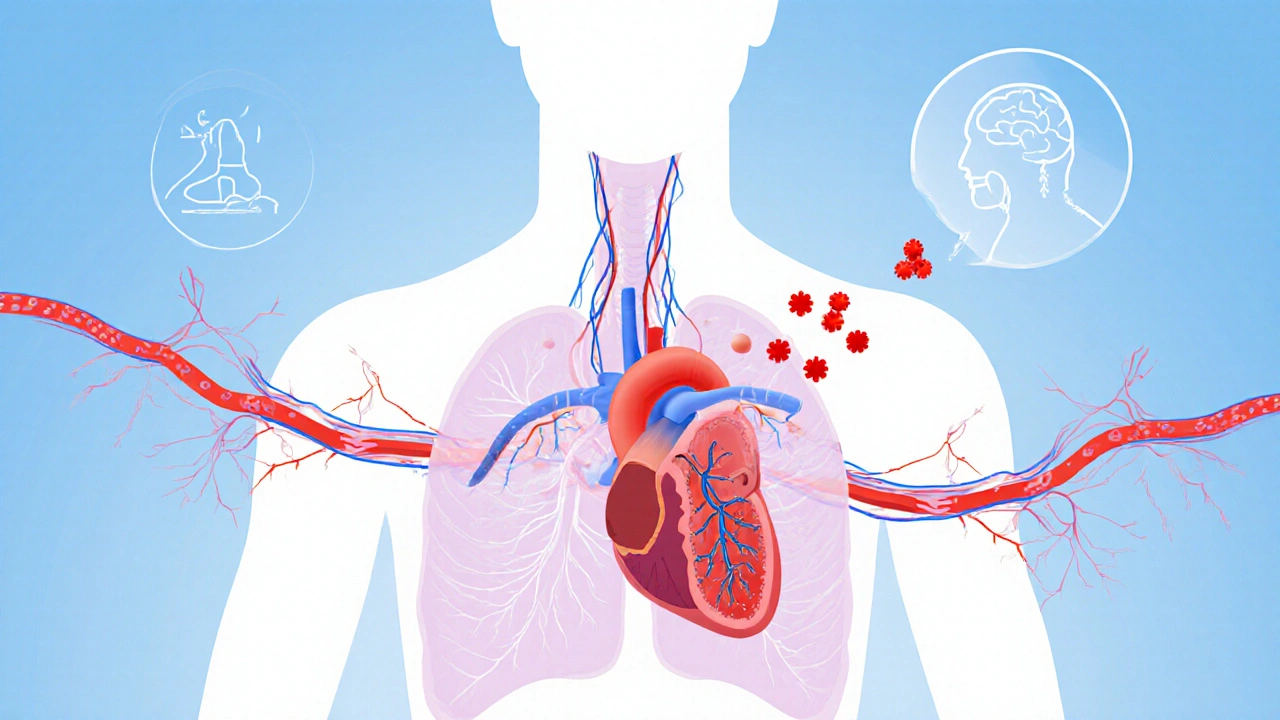

When you first stand, gravity pulls blood toward your legs. A healthy Autonomic Nervous System coordinates rapid adjustments in heart rate and blood vessel tone to keep blood pressure stable does the heavy lifting. In IOH, that system fails to respond fast enough, and systolic pressure can tumble by 20mmHg or more within three minutes of standing, causing the classic “light‑headed” feeling.

‘Idiopathic’ means doctors haven’t pinpointed a specific cause-no medication side‑effects, no blood loss, no obvious neurological disease. Roughly 5% of older adults report this pattern, but younger people can experience it too, especially after a viral infection that temporarily disrupts nerve signaling.

What Is Anxiety?

Anxiety is more than “worry.” It’s a sustained activation of the brain’s threat‑detecting circuits, releasing stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline. This response ups heart rate, narrows blood vessels in the skin, and can cause hyperventilation-all of which influence blood pressure regulation.

When anxiety spikes, the body’s Sympathetic Nervous System fires the “fight‑or‑flight” alarm, raising heart output and constricting peripheral vessels. If that surge is followed by a sudden calm, the vascular system can over‑compensate, leading to a brief dip in pressure that mirrors the dizziness of IOH.

How the Two Conditions Intersect

The overlap isn’t coincidence; it’s a physiological dance.

- Baroreflex blunting. The Baroreflex is a feedback loop that senses blood‑pressure changes and tweaks heart rate accordingly works slower in IOH. Anxiety‑driven adrenaline can temporarily mask this lag, making the brain think blood pressure is fine-until the hormone levels drop, and the delayed response shows up as a sudden dip.

- Stress hormones. Elevated cortisol from chronic anxiety can weaken blood‑vessel walls, reducing their ability to constrict when you stand.

- Breathing patterns. Hyperventilation lowers carbon‑dioxide levels, causing cerebral vessels to constrict and heightening the dizzy sensation.

- Medication cross‑talk. Some anti‑anxiety drugs (like benzodiazepines) relax smooth muscle, which can lower vascular tone and worsen orthostatic drops.

Because the symptoms reinforce each other-dizziness fuels fear, fear spikes adrenaline, adrenaline then crashes-the cycle can become self‑sustaining without proper intervention.

Overlapping Symptoms (What to Look For)

| Symptom | Typical IOH Trigger | Typical Anxiety Trigger |

|---|---|---|

| Dizziness or light‑headedness | Standing up quickly, hot environments | Panic attack, anticipatory worry |

| Heart palpitations | Compensatory tachycardia | Adrenaline surge |

| Blurred vision | Reduced cerebral perfusion | Hyperventilation effects |

| Fatigue | Repeated pressure drops | Chronic stress load |

| Feeling “off‑balance” | Autonomic dysregulation | Grounding loss during anxiety |

Practical Management Strategies

Breaking the loop means addressing both the blood‑pressure dip and the anxiety driver.

1. Gradual position changes

When moving from lying to sitting, sit up for a minute before standing. This Tilt Table Test is a clinical tool that mimics the postural shift to gauge pressure response teaches the body to adjust more smoothly.

2. Hydration and electrolytes

Aim for 2‑3L of water daily. Adding a pinch of salt (or electrolyte tablets) boosts blood volume, giving the heart more to pump when you’re upright.

3. Compression garments

Graduated compression stockings (30‑40mmHg) press the leg veins, preventing blood pooling.

4. Stress‑reduction techniques

Breathing exercises that lengthen exhalation (4‑7‑8 method) lower heart rate and keep CO₂ levels stable. Mind‑body practices like yoga or progressive muscle relaxation decrease cortisol over weeks.

5. Targeted medications

When lifestyle tweaks fall short, doctors may prescribe Fludrocortisone a mineral‑corticoid that retains sodium and expands blood volume. Midodrine is another option that directly narrows peripheral vessels. Both require monitoring for supine hypertension.

6. Review anxiety‑related meds

If you’re on benzos or high‑dose SSRIs, discuss dose adjustments with your prescriber; some agents may blunt vascular tone.

7. Regular monitoring

Keep a simple log: time of day, posture change, blood‑pressure reading (if you have a home cuff), and anxiety rating (1‑10). Patterns help clinicians tailor treatment.

When to Seek Professional Help

If you experience any of the following, schedule a medical review promptly:

- Frequent falls or near‑falls after standing.

- Syncope (brief loss of consciousness).

- Chest pain, shortness of breath, or irregular heartbeat.

- Symptoms that persist despite hydration, compression, and stress‑reduction.

- New or worsening anxiety that interferes with daily life.

Primary care physicians can order a tilt‑table test, basic blood work, and refer you to a cardiologist or neurologist for autonomic testing if needed.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can anxiety cause a drop in blood pressure on its own?

Yes. Intense anxiety triggers a surge of adrenaline followed by a rapid decline, which can temporarily lower blood pressure, especially when you stand.

Is idiopathic orthostatic hypotension treatable?

While the exact cause isn’t always known, symptoms can be managed with lifestyle changes, compression garments, and, when needed, medications like fludrocortisone or midodrine.

What’s the best way to differentiate dizziness from anxiety versus IOH?

If the light‑headedness appears within minutes of standing and improves when you sit or lie down, IOH is likely. Anxiety‑related dizziness often coincides with racing thoughts, chest tightness, or panic symptoms, regardless of posture.

Can I use over‑the‑counter salt tablets for IOH?

Salt tablets can help increase blood volume, but you should discuss dosage with a doctor, especially if you have kidney issues or high blood pressure when lying down.

Do breathing exercises really affect blood pressure?

Slow, diaphragmatic breathing raises CO₂ levels, which relaxes blood vessels and can modestly raise cerebral perfusion, easing the dizzy feeling.

Comments

carol messum

October 9, 2025 AT 22:06I’ve been thinking about how our bodies and minds can get tangled up like a knot, and this article nicely maps that out. It’s a reminder that feeling light‑headed isn’t just “in my head” – there’s real physiology behind it.

Jennifer Ramos

October 9, 2025 AT 23:46Exactly, Carol! 😊 It’s easy to dismiss dizziness as anxiety, but the overlap you mentioned shows we need to look at both the heart and the brain. Great point.

Grover Walters

October 10, 2025 AT 01:26The convergence of autonomic dysregulation and heightened cortical arousal constitutes a bidirectional feedback loop that perpetuates symptomatology. When orthostatic hypotension precipitates cerebral hypoperfusion, the ensuing anxiety amplifies sympathetic output, thereby exacerbating vascular instability. This mechanistic perspective underscores the importance of integrated assessment. Clinicians should therefore consider concurrent hemodynamic monitoring when evaluating panic‑type presentations.

Amy Collins

October 10, 2025 AT 03:06All that jargon sounds impressive but the take‑away is simple: you need a better protocol.

mas aly

October 10, 2025 AT 04:46I appreciate how you broke down the baroreflex issue; it makes the science feel more accessible. For anyone tracking symptoms, a simple log of posture changes and anxiety scores can reveal patterns worth discussing with a doctor.

Abhishek Vora

October 10, 2025 AT 06:26From a pathophysiological standpoint, the sympathetic surge during anxiety acts as a double‑edged sword. Initially, it compensates for the orthostatic drop by elevating heart rate, yet the subsequent parasympathetic rebound can precipitate a precipitous fall in blood pressure. Moreover, chronic hypercortisolemia attenuates vascular tone, rendering the baroreceptors less responsive. Evidence from tilt‑table studies corroborates this interaction, showing exaggerated heart rate variability in patients with comorbid anxiety. Therefore, treatment should not isolate one condition; pharmacologic agents like midodrine must be paired with cognitive‑behavioral strategies. Hydration and electrolyte balance remain foundational, but the psychological component demands equal attention. In practice, a multidisciplinary team yields the best outcomes. Ultimately, recognizing this interplay prevents misdiagnosis and unnecessary testing.

maurice screti

October 10, 2025 AT 08:06When one delves into the labyrinthine corridors of autonomic neuroscience, one quickly discovers that the human organism is far from the simplistic, mechanistic contraption that popular media often portrays. The interplay between the baroreceptor reflex arc and the limbic system, for instance, is an exquisite dance of electrochemical signaling that, when disrupted, manifests in the bewildering symptom complex detailed in the article. To the uninitiated, the notion that a mere orthostatic shift can cascade into a full‑blown panic episode may appear hyperbolic, yet empirical data from controlled tilt‑table experiments substantiate this phenomenon with compelling rigor. It is, therefore, incumbent upon the discerning practitioner to eschew reductionist treatment paradigms and instead adopt a holistic schema that addresses both hemodynamic stability and affective regulation. By employing graded compression garments, one can attenuate venous pooling, thereby granting the baroreceptors a more favorable operating environment. Simultaneously, mindfulness‑based stress reduction techniques have been shown to modulate amygdalar activity, which in turn tempers the catecholaminergic surge responsible for tachycardic compensation. Moreover, dietary sodium augmentation, when judiciously calibrated, augments intravascular volume without precipitating iatrogenic hypertension, a delicate balance that requires seasoned clinical judgment. One must also be vigilant regarding pharmacologic interactions; certain anxiolytics possess vasodilatory properties that could exacerbate orthostatic intolerance, a nuance often overlooked in generic prescribing guidelines. The synthesis of these considerations culminates in a therapeutic algorithm that is both nuanced and patient‑centered. In practice, this translates to a regimen wherein the patient rises slowly, hydrates adequately, dons compression stockings, and engages in daily diaphragmatic breathing exercises-all under the watchful eye of a multidisciplinary team. While this may appear onerous to some, the long‑term dividends of reduced syncope, diminished fall risk, and enhanced quality of life are indisputable. Ultimately, the convergence of idiopathic orthostatic hypotension and anxiety is not a mere coincidence but a testament to the intricate interdependence of physiological and psychological domains, a perspective that should inform both research and clinical stewardship.

Abigail Adams

October 10, 2025 AT 09:46Your exposition, while impressively erudite, borders on the pedantic and may alienate patients seeking straightforward guidance. It would be beneficial to distill these recommendations into a concise, actionable checklist.

Belle Koschier

October 10, 2025 AT 11:26I love the balanced tone of the piece – it neither downplays the seriousness nor induces panic. Sharing personal anecdotes about successfully using compression socks could further empower readers.

Allison Song

October 10, 2025 AT 13:06Indeed, narrative experiences often bridge the gap between clinical advice and daily practice. When individuals describe the “first‑light” feeling dissipating after a gradual sit‑to‑stand routine, it validates the physiological explanations provided.

Joseph Bowman

October 10, 2025 AT 14:46They don’t tell you that the pharmaceutical industry pushes meds to mask these natural feedback loops. Keep reading between the lines.

Singh Bhinder

October 10, 2025 AT 16:26The article mentions midodrine but doesn’t discuss its side‑effects much. Does anyone have practical tips on monitoring for supine hypertension while on it?

Kelly Diglio

October 10, 2025 AT 18:06Monitoring blood pressure at home, especially after lying down for a few minutes, can reveal the nocturnal hypertension that sometimes accompanies midodrine therapy. Pairing these readings with a simple anxiety rating scale each evening creates a dual‑parameter log that clinicians find invaluable. Additionally, ensuring adequate potassium intake can mitigate the risk of arrhythmias associated with increased vascular tone. It is also prudent to schedule follow‑up appointments every three months to reassess dosing. Ultimately, a collaborative approach between patient and provider fosters adherence and safety.

Carmelita Smith

October 10, 2025 AT 19:46Great tips, Kelly! 👍